Meet Drexel Writing Festival Author Iván Monalisa Ojeda, Trans Essayist, Poet and Performer

By Liz Waldie

April 8, 2024

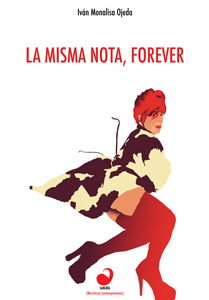

Iván Monalisa Ojeda was born in the late sixties in southern Chile and grew up on the shores of Lake Llanquihue. He/she studied theater at the University of Chile, in Santiago, and when he/she got his/her degree, Iván Monalisa settled in New York, where he/she currently lives. He/she published an essay collection, La Misma Nota, Forever (

Sangria Publishers, 2014) and has written articles for magazines and plays. In addition to being a writer, he/she is a performer and is at work on another collection of short stories. Iván Monalisa's pronouns are he/she, his/hers, him/her because he/she considers him/herself to be both genders.

Iván Monalisa will read at the Drexel Writing Festival on

Monday, April 15 at 3:30 p.m. Read the full Q&A below to learn about Iván Monalisa's creative process, upcoming works and more.

You’re both a performance artist and an author. What drew you to these two areas and how do they influence each other?

You’re both a performance artist and an author. What drew you to these two areas and how do they influence each other?

First, I was first in law school for three years, but it was not for me, so I went to drama school in Chile. I had been writing since I was a kid, since I had memory, so one of the things that I started to do was write plays. When I came to New York in 1995, art, performance, stage and writing came together. That is a play. It’s like taking a short story or novel and putting it on stage. For me, they are together. I tried to get into how important emotions are, because as an actor, you try to play or perform the emotion of the character. And as a writer, it’s how you describe this emotion. At the end, you have a mixed salad of emotion that makes a story. So those two things—performing and writing, in my case—come absolutely together. One of the steps that I take to make me feel like a short story is done and ready to be published is I read to my friends. For me, it’s very important how I communicate and express what I’ve written. When I read and voice what I wrote and I have people listening to me, I get their reaction: that’s when I feel that my work is good. This is performing and literary at the same time. If I didn’t have the theatrical experience, I don’t think I would write how I’ve written. It gave me the technique that I can use on the stage and in my books.

Your written work touches on themes such as drug addiction, gender identity, sex work and immigration. Why did you focus on those topics?

As a writer, as an author, you have to write about what you see, what you feel, what is around you in your space, the society and tribe that you live in. Human beings have to make a register—write in stone—what is happening around them. That’s what I think an author is supposed to do. I think authors have a social obligation with society. It’s what I have to leave. I have to talk about it. Everything has already happened, but as an author, you have the technique to put it into a book. That’s what it is to be a storyteller. What is fiction and what is reality? Fiction comes from reality.

What does your creative process look like? How do you approach writing about personal and sometimes painful issues?

One of the first things you learn when you study drama is, “Don’t judge the character.” Whether it is a bad or good character, you have to be an instrument and do what the playwright tells you to do. You accept the character the way it is. You don’t judge them. The same situation applies when you write. You just write what you see, and you don’t assign moral values. Maybe the situation can be terrible, or it can be good, but the readers are the ones who are going to judge and put emotion to the situation. What I like about my community is that we always see the joyful or the happy part of the situation. That’s what makes us learn things. In the LGBT community, the transgender community is a strong one. So it’s not difficult for me. It’s not a moral thing. It’s important. As an artist, you don’t judge. There’s no fear in telling the scenes the way they are.

Have you faced any challenges in the publishing or performance industries due to your identity? How did you overcome these challenges?

When I was in Chile, as a performing artist, there was a lot of prejudice, and I didn’t realize my transgender identity at the time—I thought I was just gay. I got a lot of funny faces, attitude, sometimes they didn’t let me do my work. There was a lot of jealousy. But some people adored me and loved me, and I was awarded grants and connections, so I was still able to do my work. In 1995, Chile was just getting out of a dictatorship, bloodshed, and all this fascist attitude. I remember when I came back to southern Chile before coming to New York, it was a nasty place. But fortunately, not here in New York. I have faced no discrimination here.

What’s next for you?

I’m working on my next book of short stories. It focuses on the pandemic, drug addiction, things my friends are going through, and homelessness and the system—something that happens here is that you must be in really bad shape in order for the system to help you.

What will you be reading at the Drexel Writing Festival, and why?

I will be reading a play I wrote decades ago. I haven’t written plays in a long time, and I wrote this one in English—it’s not translated. It’s easier for me to write drama in English, because it’s just dialogue. This play is called Waiting for the Night and is a story about a love relationship between two immigrants, one of which is a South American sex worker who lives in New York. This was in a box for so many years, but I think it’s a good thing. For me, it’s kind of like returning to the station in some way.