5 Things You Should Know About Ebola Virus

By Katie Clark

By Katie Clark

October 2, 2014

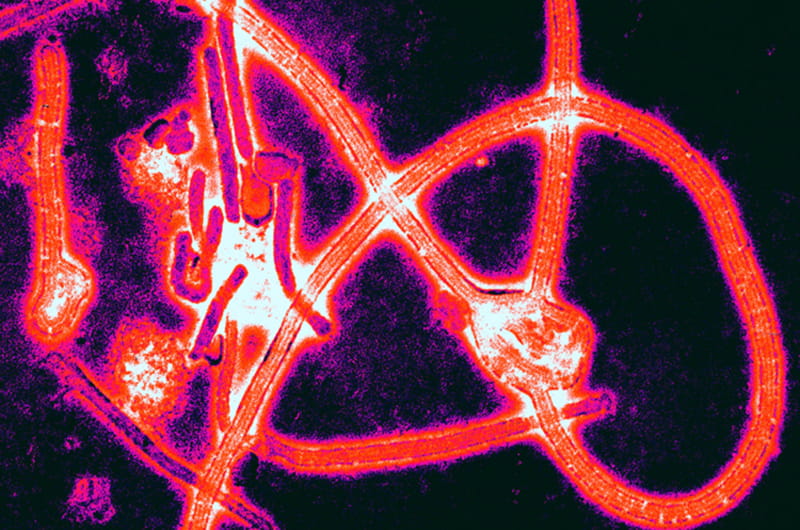

Color-enhanced close-up of Ebola virus particles. Photo by Thomas W. Geisbert

Last week, the first case of the Ebola virus was confirmed in the United States, a fact that has no doubt caused concern as the number of fatalities in West Africa continues to rise. In an effort to get a little more educated about the disease and its threat now that it’s reached the U.S., DrexelNow looked to Esther Chernak, MD, an infectious disease physician and associate professor in the School of Public Health, to provide some insight.

- The current outbreak of Ebola virus disease in West Africa is unprecedented in scope. There have been over 20 outbreaks in Africa since the virus was first described in 1976, all of which were relatively limited in size. This outbreak is the only one that has spread to multiple countries. Prior outbreaks had been limited and generally affected no more than 500 people.

- Ebola virus is transmitted through contact with the blood or body fluids of an infected person who is symptomatic. People who have been exposed but who are not symptomatic are not contagious. It is not spread through the air, through food or through water. Air travel is an important potential mechanism for the global spread of this disease because people can travel after an exposure to the virus during the long (up to 21 days) incubation period. But because people with the disease are not infectious until they are symptomatic, public information and efforts to screen for fever and symptoms prior to getting on an airplane will keep air travel itself safe for others who are flying.

- There is no specific treatment for Ebola virus, and no vaccine to prevent disease. Spread in communities is stopped by isolating infected people and ensuring that others who have physical contact with them are protected with barriers like gloves and gowns. All of the close contacts of Ebola cases must be identified and their health must be monitored closely for 21 days to ensure that signs of the disease are recognized early so they do not pose a threat to others. The best line of defense is a strong health care system, a strong public health system, and an informed public that understands how it is spread and who is at risk.

- Ebola virus is not likely to spread in Texas, or anywhere else in the United States, including Philadelphia, even if additional travel-related cases occur, which is quite possible. Once it is recognized, the infection control measures necessary to contain it are well understood and readily available in health care facilities in this country. And the public health system here has great capacity to identify contacts of cases and monitor them to prevent transmission.

- The magnitude and severity of the current West African outbreak is the result of a devastating perfect storm: countries with weak health care systems, profound poverty, traditional cultural practices such as the bathing of corpses before burials and touching them during funerals, and a legacy of government distrust after years of civil war, colonialism and corruption. This outbreak is now a humanitarian catastrophe – a slow motion tsunami – with problems above and beyond casualties from Ebola, as health care services and economies unravel.

We are already witnessing a rise in vaccine preventable diseases, complications of pregnancy, and untreated chronic diseases as access to primary medical care disappears. The major industries of Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea are suffering and unemployment is now a problem throughout the region. The events in West Africa are a tragic illustration of how investment in public health and health care is an inextricable component of development, and how global disparities in health care resources are both a human rights issue and a threat to global health security.

Drexel News is produced by

University Marketing and Communications.

now.editor@drexel.edu

For story suggestions or to share feedback

now.webmaster@drexel.edu

For questions concerning the website, or to report a technical problem